John Wycliffe

In the reign of Edward the Third, a crowd of the citizens of London were seen on their way to old St. Paul's. As they hurried along the narrow streets, and collected around the doors of the cathedral, their loud voices and violent actions, showed that they were engaged in angry debate. It was evident that some unusual event had  drawn them from their homes so early on that winter's morning.

drawn them from their homes so early on that winter's morning.

A priest, named John Wycliffe, was about to appear, to answer charges that had been brought against him. As they gathered into clusters the accused arrived, dressed in a plain black robe, with a small round cap on his head. His long grey beard spread over his breast. He looked calm, as though the tumult of the people awoke in him no fear. Passing through the throng, he entered a small ancient chapel, which formed a part of the cathedral, where a bishop and the judges had already taken their seats. The accused was not alone. Two noblemen, clothed in velvet and gold, walked by his side. One of them, the Duke of Lancaster, placed himself on his left hand; the other, Lord Percy, stood on his right. When the popish judges saw the powerful friends who had come to support his cause, they were filled with rage; and charged the two noblemen with being enemies to their religion and the king. Provoked by these words, the duke, in return threatened the bishop, and soon the whole assembly was in confusion, John Wycliffe standing all the while before his judges without speaking a word.

When the people who were at the doors heard the noise within, they cried aloud against the good priest; then running through the streets to the palace of the Duke of Lancaster, the most beautiful mansion in the kingdom, they began to pull it down. In their rage they committed murder on a person that was passing near the spot.

Those ignorant people had been told by some designing priests that Wycliffe and his friends intended to destroy the religion of the land, and in their ignorance they were driven to these acts of violence. It was like the scene when the apostle Paul was at Ephesus; "and the whole city was filled with confusion," because the idol-makers, who feared they should lose their gains, stirred up the people to oppose the preaching of the gospel.

Nearly twelve months passed away, and Wycliffe once more stood in the same place, and before the same judges. There was again a great crowd of people; but they were not then crying out against him, and demanding that he should be sent to prison. Since the pious priest was last there they had better understood his character, and had learned to value his preaching. He was now known to them as the "gospel doctor."

The people had come to support his cause. They forced their way before the court, and demanded that he "should not be hurt." The priests were alarmed at what they saw and heard; and though they had hoped to have condemned him, they were glad to let him depart freely to his home.

Is it asked, What was the crime that brought Wycliffe into such trouble? The answer is—The pope of Rome had sent three letters, or "bulls" as they were called, to England—one to the bishops, another to the university of Oxford, and a third to the king. In them he charged the humble parson with many serious offenses; and he desired that he should be seized and sent to prison, there to lie until further orders from Rome. Was he, then, a teacher of false doctrine, a traitor, or in any other way a wicked and injurious man? No; his offense was, that he was an inquirer after truth, and sought to bring the people from under the power of the monks and friars, who led them astray; and it was because he thus felt and acted that the pope had resolved on his overthrow.

Is it asked, What was the crime that brought Wycliffe into such trouble? The answer is—The pope of Rome had sent three letters, or "bulls" as they were called, to England—one to the bishops, another to the university of Oxford, and a third to the king. In them he charged the humble parson with many serious offenses; and he desired that he should be seized and sent to prison, there to lie until further orders from Rome. Was he, then, a teacher of false doctrine, a traitor, or in any other way a wicked and injurious man? No; his offense was, that he was an inquirer after truth, and sought to bring the people from under the power of the monks and friars, who led them astray; and it was because he thus felt and acted that the pope had resolved on his overthrow.

There were at this time in England many thousands of persons called monks and friars. The monks were those who lived alone or separate from other people; their houses were called monasteries, or places of retirement; the term friars signifies "brothers." Of these latter were the begging friars, who, it is said, "swarmed throughout England" at this time. They traveled over the land, forcing their way into the houses of rich and poor, living without any cost, and taking all the money they could obtain. Though they assumed poverty, they were not "poor in spirit;" nor were they "the meek of the earth." Like the Pharisees of old, they pretended to be better and holier than others, though their lives were full of evil. They "taught for doctrine the commandments of men," and declared that all who belonged to their order were sure of salvation.

When Wycliffe saw the conduct of the friars, his heart was much grieved. The best way to oppose them he knew would be to write a book against them; and a book was written in which he called them, "the pests of society, the enemies of religion, and the promoters of every crime." Angry and annoyed at the exposure, they were ready to help the pope in the hope of getting the writer sentenced by the judges to the dungeon or to death. Wycliffe, however, continued to write and preach against them, and with so much labor and zeal that his health began to suffer. One day, lying on his bed, and, as it was thought, nigh to his end, some of these friars made their way into his room. They rushed to his couch, began to upbraid him for what he had done, and called on him to express his sorrow before he died. For some time he heard them in silence; then, desiring his servants to raise him up, he cried aloud, "I shall not die but live, and shall again declare the evil deeds of the friars." Alarmed at his courage, they fled in haste from the room.

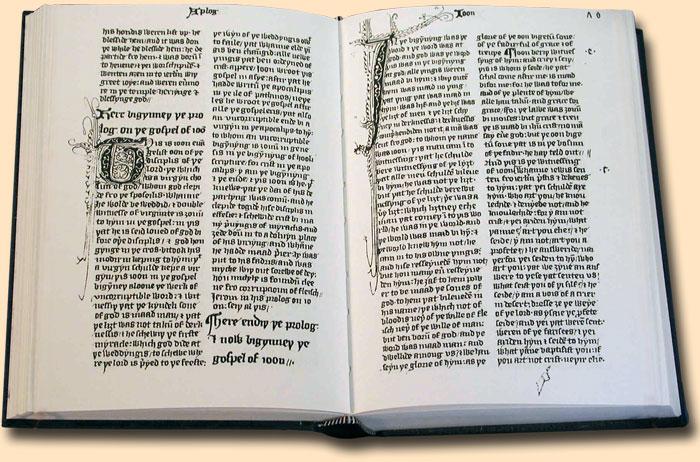

When Wycliffe got well, he retired to the little market town in Leicestershire, of which he was the priest. In this place he entered on his great work—that of translating the Bible into the English language as it was then spoken. To give the people the word of God was the best way of fulfilling his threat against the friars. He knew that the Bible was God's great gift to the whole human family; why, then, should not his countrymen possess it? To give it to them would be something worth living for; and so he diligently set about his task.

as it was then spoken. To give the people the word of God was the best way of fulfilling his threat against the friars. He knew that the Bible was God's great gift to the whole human family; why, then, should not his countrymen possess it? To give it to them would be something worth living for; and so he diligently set about his task.

It was a long and difficult work to undertake; but faith and love carried him through it. The word of God was precious to his own soul; and he knew that what had been a blessing to himself could be made a blessing to thousands. So onward he went in his work, with prayer and patience: and as he went along, he found instruction and comfort for himself, whilst he was providing for the spiritual good of others.

Year after year he saw the fruits of his study increase: one page and then another were done, until, at length, in the year 1380, the last verse of the New Testament was translated, and the Bible completed in its English dress! We may think we see him looking upon the pile of writing he had made, then falling on his knees to give God thanks, imploring him to bless the truth to the souls of the people.

~ Part 2 Next Month ~

Copied by Stephen Ross for WholesomeWords.org from Historical Tales for Young Protestants

There is a voice of Truth which can be heard crying out! Whether lost or saved, we believe you will meet the living Christ through this ministry.

There is a voice of Truth which can be heard crying out! Whether lost or saved, we believe you will meet the living Christ through this ministry.