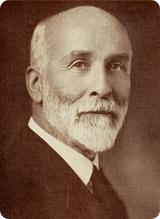

Jonathan Goforth

Friends, if you and I take glory to ourselves which belongs only to God, we are as foolish as the woodpecker about which I shall tell you. A certain woodpecker flew up to the top of a high pine tree and gave three hard pecks on the side of the tree, as woodpeckers are wont to do. At that instant, a bolt of lightning struck the tree, leaving it on the ground a heap of splinters. The woodpecker had flown to a tree nearby where it clung in terror and amazement at what had taken place. There it hung expecting more to follow, but as all remained quiet, it began to chuckle to itself saying, "Well, well, well. Who would have imagined that just three pecks of my beak could have such power as that! That was one of Jonathan Goforth's favorite stories and with good reason. Few Christians have been so tempted to carnal pride as was he, for few have been the human instrument of such remarkable revivals or the object of such praise. A Roman Catholic servant girl, in a home where the Goforth's often revisited, said, "I have often watched Dr. Goforth's face and wondered if God looks like him." Charles G. Trumbull said of him, “He was an electric, radiant personality, flooding his immediate environment with sunlight that was deep in his heart and shone on his face. And God used him in mighty revivals."

Friends, if you and I take glory to ourselves which belongs only to God, we are as foolish as the woodpecker about which I shall tell you. A certain woodpecker flew up to the top of a high pine tree and gave three hard pecks on the side of the tree, as woodpeckers are wont to do. At that instant, a bolt of lightning struck the tree, leaving it on the ground a heap of splinters. The woodpecker had flown to a tree nearby where it clung in terror and amazement at what had taken place. There it hung expecting more to follow, but as all remained quiet, it began to chuckle to itself saying, "Well, well, well. Who would have imagined that just three pecks of my beak could have such power as that! That was one of Jonathan Goforth's favorite stories and with good reason. Few Christians have been so tempted to carnal pride as was he, for few have been the human instrument of such remarkable revivals or the object of such praise. A Roman Catholic servant girl, in a home where the Goforth's often revisited, said, "I have often watched Dr. Goforth's face and wondered if God looks like him." Charles G. Trumbull said of him, “He was an electric, radiant personality, flooding his immediate environment with sunlight that was deep in his heart and shone on his face. And God used him in mighty revivals."

It was as true of Goforth as of Robert M. M'Cheyne that all who knew him "felt the breathing of the hidden life of God." He knew the folly of self-reliance. He knew whence power came and to whom the

praise belonged. So as a young man he chose Zechariah 4:6 as his life's motto.

The sunlight in his heart! The divine reflection on his face!

The breathing of the hidden life of God! "Not by might, nor by power, but by my spirit, saith the LORD."

Everything in the character and career of this amazing man can be outlined in terms of the work and witness of the Holy Spirit in his yielded, trusting life.

Jonathan Goforth, the seventh of eleven children, was born February 10, 1859, on his father's farm near London, Ontario, Canada. His devout mother influenced him to pray and to love and to read and memorize the Scriptures. Something of the hardships endured by the family is indicated by the fact that the father once went to Hamilton for food and walked through the bush all the way back, a distance of seventy miles, with a sack of flour on his back. By diligent effort, Jonathan managed to keep up with his class in school, although he was under the handicap of being obliged to work on the farm each year from April to October.

When he was fifteen years of age, his father put him in charge of their second farm which was twenty miles from the home farm. "Work hard," said his father. "At harvest I'll return and inspect." In later years, Goforth stirred many an audience as he told of his arduous labors that summer, of his father's return in the fall, and of how his heart thrilled when his father, after inspecting the fields of beautiful waving grain, turned to him and smiled. "That smile," he would say, "was all the reward I wanted. I knew my father was pleased. So will it be, dear Christians, if we are faithful to the trust our Heavenly Father has given us. His smile of approval will be our blessed reward."

At the age of eighteen, while Jonathan was finishing his high school work, he came under the influence of Rev. Lachlan Cameron, a true minister of Christ. He went one Sunday to Rev. Cameron's church and heard a sermon from God's Word that cut deeply and exactly suited his need. The Holy Spirit used the Word to bring him under conviction and that day he yielded to the tender constraints of Christ. "Henceforth," said he, "my life belongs to Him who gave His life for me."

Under this impulse, he became an active, growing Christian. He sent for a supply of tracts and startled the staid Presbyterian elders by standing Sunday after Sunday at the church door, giving each person a tract. Soon thereafter, he began a Sunday evening service in an old school house about a mile from his home. He instituted the practice of family worship and besought the Lord for the salvation of his father. Several months later his father took a public stand for Christ.

About this time, his faith was subjected to a severe testing. His teacher was a blatant follower of the infidel Tom Paine, and his classmates, influenced by the teacher, made his life miserable by their jeers and mockery. The foundations seemed to be giving way and in a mood of desperation Jonathan turned to God's Word. In consequence of an earnest, day-and-night search of the Word, his faith was firmly established and all his classmates, also his teacher, were brought back from infidelity. The next great influence in Jonathan's life came through a book and then a collection of books. A saintly old Scotchman, Mr. Bennett, one day handed him a well-worn copy of the Memoirs of Robert Murray McCheyne, saying, "Read this, my boy; it will do you good." It did! Stretched out on the dry leaves in the woods, he was soon so absorbed in the book he did not notice the passing of the hours. When the lengthening shadows of sunset aroused him, he arose a new man. The story of McCheyne's spiritual struggles, sacrifices, and victories stirred him to the depths and was used of God's Spirit to turn his life from selfish ambitions to the holy calling of being a seeker of souls. In view of his intention to enter Knox College to prepare for the ministry, Rev. Cameron arranged to give him lessons in Latin and Greek. He also loaned him a number of books by Bunyan, Baxter, Boston, and Spurgeon. Goforth "devoured" them with rich blessing. But his main book was the Bible. He arose two hours earlier each morning in order to have unhurried time for the study of the Word before going to work or to school.

Young Goforth was now spiritually ready for God to deal with him again. One epochal day, he went to hear an address by the heroic missionary pioneer, George L. Mackay of Formosa. Full of the Holy Spirit, like Peter and Paul and Stephen of old, Dr. Mackay pressed home the needs and claims of the heathen world, especially of Formosa. He told how he had been going far and wide in Canada, seeking missionary reinforcements; but so far, he had not found even one young man willing to respond. Simply but powerfully, he continued, "I am going back alone. It will not be long before my bones will be lying on some Formosan hillside. To me the heartbreak is that no young man has heard the call to come and carry on the work that I have begun."

As Goforth heard these words he was "overwhelmed with shame." He describes his reactions as follows: "There was I, bought with the precious blood of Jesus Christ, daring to dispose of my life as I pleased. Then and there I capitulated to Christ. From that hour I became a foreign missionary."

Note well the words, "From that hour I became a foreign missionary." An ocean voyage does not transform a lukewarm Christian into a glowing brand for God.

Jonathan's mother was a capable seamstress and in the last days before his departure for Knox College she often worked far into the night preparing his wardrobe. Little did she imagine how the cut of his garments and the fine hand stitches would cause him to be an object of ridicule in the city. He arrived at the college with ardent expectations concerning the friendly reception and Christian fellowship that awaited him. However, he was soon disillusioned by the glances and guffaws of the students. Despite his very limited finances, he determined to alter the situation. He purchased a quantity of cloth which he planned to take to a city seamstress in order to have a new outfit made. Learning what he had done, his college mates one night took him from his room by force, put his head through a hole they had cut in one end of the material and made him drag the cloth up and down the hall through a gauntlet of hilarious students. In his humiliation that such a thing could happen in a Christian college, he spent hours over his Bible and on his knees in the first great struggle of his life.

On his first day in Toronto, Jonathan walked through the slum section praying that God would open a way whereby he might take the Gospel to the needy homes and hearts of that area; and the first Sunday morning found him preaching in a jail – a practice he continued throughout his college course. An unreservedly, as his studies would allow, he gave himself to evangelistic calling in the homes of the slums and to the work of different rescue missions. The stories he told of his experiences with degraded sinners caused much mirth among the students. It is significant, however, that later the students of Knox College sent him out to China as their missionary – a remarkable tribute to the reality and power of his Christian character.

He exhibited a fervent zeal for souls. At the opening of a new fall session at college, the principal asked Jonathan how many homes he had visited during the summer vacations. "Nine hundred sixty," was the reply. "Well, Goforth, if you don't take any scholarships in Greek and Hebrew, at least there is one book that you are going to be well versed in and that is the book of Canadian human nature." Indeed, not only were many souls saved but many valuable lessons learned, for as he discovered later, there is no essential difference between Canadian and Chinese human nature. During his years in college and in slum work, he was often down to the last penny; but God proved faithful in every test. Like George Mueller and Hudson Taylor, he learned to trust God utterly for all his needs.

He also learned to trust the Spirit's guidance in all circumstances. On one occasion, when scheduled to speak at a certain place on Sunday, he found he had only sufficient money to buy a ticket one station short of where he was to speak. After praying for divine guidance he bought the ticket and rode to that station, then began to walk the remaining ten miles. When he had covered approximately eight miles, he came upon a group of men repairing the road. He engaged them in friendly conversation, pointed them to the only "name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved", and invited them to the service the following day. To his great joy, several of them turned up and at least one of them was saved. In referring to this later he would say, "I would gladly walk ten miles any day to bring one lost soul to Christ." He was indeed a missionary long before he reached China. It was said of him, "When he found his own soul needed Jesus Christ, it became a passion with him to take Jesus Christ to every soul."

He did not hesitate to enter saloons and brothels. In these places, he won for Christ a number of broken, disreputable persons. One night as he was coming out of a street that had a particularly evil reputation, a policeman met him and said, "How have you the courage to go into those places? We policeman never go there except in two's or three's." "I never walk alone, either," replied Goforth. "There is always Someone with me."

At one time he was walking along the road from Aspidin to Huntsville, a distance of ten miles, calling at every house. Years later, a lady wrote of the abiding blessings that ensued upon the visits of this "Spirit-filled young man" and she concluded, "He walked in the power of the Holy Spirit."

"I never walk alone! I would walk ten miles any day to bring one soul to Christ!" He walked in the power of the Holy Spirit!

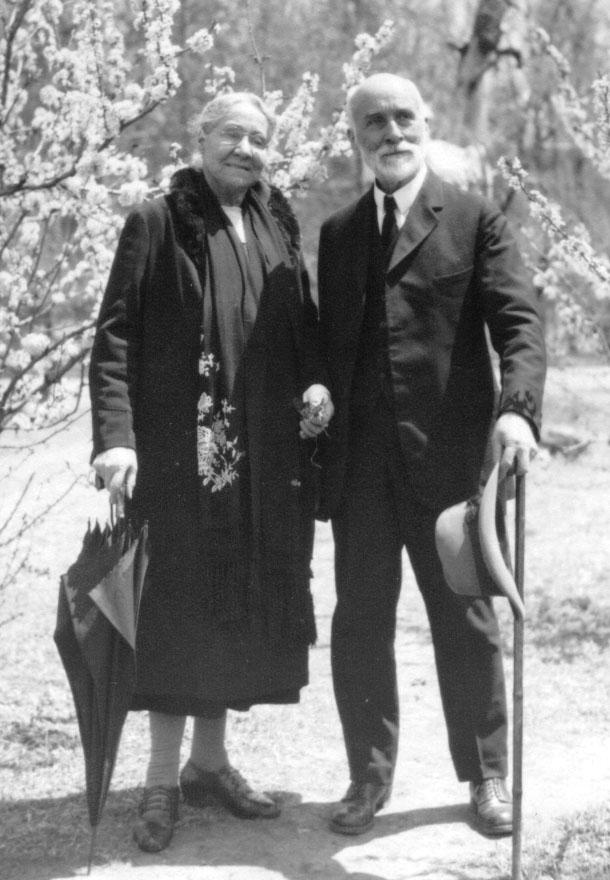

It was in connection with his mission work in Toronto that Goforth met Rosalind Bell-Smith. She was an Episcopalian, a member of a cultured and wealthy family, and an artist. She was also a born-again Christian and longed to live a life of service to God. The day she met Goforth, she noted both the shabbiness of his dress and the challenge of his eyes. A few days later at a mission meeting, she picked up Jonathan's Bible, which was lying on a chair, observed that it was marked from cover to cover and noted that parts of it were almost in shreds from frequent use. "That's the man I want to marry," she said to herself. A few months later she accepted his proposal of marriage upon the condition he himself stipulated, namely, that in all things he should put his Master's work before her. Little did she dream what that promise would cost her through the long years ahead. The first, though not the greatest, price it cost her was the engagement ring of which she had dreamed. Jonathan explained that he needed every penny for his ministry of distributing Testaments and tracts. "This," she said, "was my first lesson in real values."

In the spring of 1887, Goforth went to scores of churches to plead the cause of China. He was on fire for missions and his holy enthusiasm melted thousands of indifferent hearts. When he was speaking on the needs and claims of the unevangelized worlds, he had the face of an angel and the tongue of an archangel. He used many methods – Scripture, charts, pictures, logic – to enforce his message. He often closed an address by a powerful illustration from the feeding of the five thousand. He pictured the disciples taking the bread and fish to the hungry people on the first few rows, then going again and again to those same people, leaving those on the back rows hungry and starving. Then he would ask a burning question, "What would Christ have thought of His disciples had they acted in that way, and what does He think of us today as we continue to spend most of our time and money in giving the Bread of Life to those who have heard so often, while hundreds of millions in China are still starving?"

Years later, when Goforth was home on furlough and speaking in a Presbyterian church in Vancouver, the minister who was introducing him said, "This man took an overcoat from me once." He went on to explain how he had gone to Toronto to buy a new overcoat and how, at a missionary meeting, he was stirred as never before upon listening to the impassioned appeal of Jonathan Goforth. "My precious overcoat money went into the missionary collection," continued the minister, "and I returned home wearing my old coat."

October 25, 1887, Jonathan and Rosalind were married. After a memorable farewell service in the historic Knox church of Toronto, the Goforth's sailed for China, February 4, 1888, under the auspices of the Presbyterian Church of Canada.

The Goforth's settled first at Chefoo for nine months of language study. While living there, some valuable lessons were learned. About two weeks after settling in Chefoo, their house burned to the ground and practically everything they had was destroyed. Mrs. Goforth was distraught, but her husband simply said, "My dear, do not grieve so. After all, they're just things." Thus Rosalind learned another lesson in real values. It was also at Chefoo she learned a lesson in tithing. She had considered themselves generous in tithing their missionary salary. But when they had been married six months, it was discovered they had already given a tenth of a year's salary. "We'll simply close the account and keep on tithing," he said. So they gave two tithes instead of one.

With elation of spirit, the Goforth's moved further and further into the interior on the way to the remote province of Honan to set up a home and a mission station. Their early years in China were marked by sweet joys, piercing sorrows, and significant manifestations of character. Chief sorrows were connected with the untimely passing of their first two children. Their severe heartache was swallowed up in their travail over the woes of the Chinese masses. The word "without" was written in giant letters over the blackness of heathenism on every side as the Goforth's moved along.

Men and women are toiling without a Bible, without a Sunday, without prayer, and without songs of praise. They have homes without peace, marriages without sanctity, little children without innocence, young men and girls without ideals, poverty without relief or sympathy, sickness without skillful help or tender care, sorrow and crime without remedy, and death without hope.

Before reaching Honan, Goforth had received a cordial letter from Hudson Taylor, telling him of the tremendous obstacles ahead and reminding him of his need of super-natural assistance. "Brother, if you would enter that province," Taylor wrote, "you must go forward on your knees." Goforth did just that. Not a day passed but that circumstances and events caused him to recall his life text and to rely on its promise, "Not by might, nor by power, but by my Spirit, saith the LORD of hosts" (Zechariah 4:6).

By means of prayer and dependence upon the Holy Spirit, he witnessed and experienced many miracles. One of these was in connection with language study. In college in Toronto, he was weak in languages. In China, he made little progress in the use of the language, although he applied himself to the task with great diligence. Repeatedly, when he was trying to preach to a group of people, the Chinese would point to another missionary who had reached China a year after he did, and say, "You speak. We don't understand him." This was mortifying, but Goforth refused to be discouraged. "The Lord called me to China,” he said, "and I expect His Spirit to perform a miracle and to enable me to master the language." He picked up his Chinese Bible and went to the chapel. As he began to preach the miracle happened; He spoke with a fluency and power that amazed the people. Thence forth, his mastery of the Chinese language was recognized everywhere. Two months later, he received a letter from Knox College telling of a prayer meeting in which the students prayed "just for Goforth" and the presence of God was manifestly among them. Looking into his diary, he found that the prayer meeting was at the very time his tongue gained such sudden mastery over the Chinese language.

Part 2

It was as true of Goforth as of Robert M. M'Cheyne that all who knew him "felt the breathing of the hidden life of God." His zeal for souls caused him to be away from home much of the time in widespread evangelistic itineration. He often spent the night in places that were disagreeable for lack of heat and for other reasons. For instance: "One end of the small room I occupied was for the pigs and the donkeys. Besides, we had to contend against other living things not so big as donkeys, but a thousand times more troublesome." There were many escapes from wild mobs. One day, he and a colleague came suddenly into a crowd of thousands attending a sort of fair. Though both foreigners wore Chinese dress, their identity was soon recognized and in a few moments the crowd rushed upon them, hooting, yelling, throwing sticks, stones, and clods of earth. Just when death seemed imminent, a sudden gust of wind blew a tent over and scattered the articles offered for sale. As the Chinese scrambled for these, the missionaries escaped.

A common method of transportation was to ride in a hired wheelbarrow. Goforth soon found out, however, that if he rode, his Chinese helpers also insisted on riding although they had never before been accustomed or able to do so. To defeat this pride, he bought a barrow for four dollars and hired a man to wheel it for about fifteen cents a day. He wrote,

“I shall not allow myself a ride on this barrow nor shall I allow a Chinese the luxury. I am determined to walk. The barrow conveys books and baggage, not missionaries. My expenditure, including the barrow man's hire, amounted to twenty-four cents a day for the thirty-three days of my tour.”

This intrepid missionary constantly lived up to his name, for he was ever eager to "go forth" to new areas and new conquests for Christ. In 1894, and 1895, he went to Changte in remote North Hogan, bought land, erected buildings, established a mission station, and moved the family belongings. This was, for the Goforths, the seventh home in their seven years in China. Even before settling in the seventh home, the mission compound was covered by flood waters to a depth of more than six feet, and thus for the second time, they experienced the loss of practically all of their temporal possessions.

The air was filled with wild rumors about the foreign devils. One of these was to the effect that the medicine used by the foreigners in treating the people was made from the hearts and eyes of kidnapped Chinese children. But the Spirit of God was at work and such crowds waited upon the ministry of the Word that both Goforth and his wife "kept up constantly preaching on an average of eight hours a day" and were at the point of complete physical exhaustion. Early one morning he said, "Rose, on the basis of Philippians 4:19, let us kneel down and pray for an evangelist to help us in the work." This they did, though as yet they had not a single convert in this area. The next day, a man named Wang Fulin appeared at the Mission seeking employment. He was a pitiable spectacle, his face having the ashy hue of an opium fiend, his form bent from weakness, and his emancipated frame clothed in a beggar's rags and shaking every few moments from a racking cough. This man became a mighty testimony to the transforming power of Christ and a fervent preacher of the Gospel. In the first five months at Changte, about twenty five thousand men and women visited the compound and heard the precious tidings of redemption proclaimed by the Goforths and the converted gambler and opium smoker Wang Fulin.

When their new semi-foreign bungalow was completed, the Chinese came in swarms to see the board floors, glass windows, the furniture, sewing machine, and the organ. The kitchen stove, which sent its smoke up the chimney instead of into people's eyes and all over the house, was an object of constant wonder. The pump was the talk of the whole countryside. What a contraption that could bring water up from the bottom of a well with out a bucket! As many as 1,835 men and 500 women passed through the house on a single day and all heard the Gospel message.

Rosalind frequently played the organ to the great delight of the Chinese. Jonathan, however, did not know one note from another. Imagine her surprise and amusement when, upon returning from an errand one day, she found her husband seated at the organ with all twenty-four stops drawn out, his hands pressed down on as many notes as possible, the bellows going at full blast, and heard some one remark above the din, "He plays better than his wife!"

By this time they had three living children to rejoice their hearts. Then, in the summer of 1898, little Gracie was found to be in a hopeless condition from an enlarged spleen caused by pernicious malaria. For almost a year, she lingered and suffered. One night, Grace sat up in bed and said, "I want my Papa." Rosalind hesitated to call the worn out father but when Grace said again, "I want my Papa," she roused him. As the father took the little one in his arms and began to pace the floor, Rosalind went into another room and prayed that God would heal the dear child or spare her from further suffering. While the mother was on her knees, Grace sudden lifted her head from father's shoulder, looked straight into his eyes, gave him a wonderful smile, closed her eyes and in an instant was in the Savior's arms.

Goforth was singularly adept at devising ways of meeting difficult situations and appealing to various types of people. At a certain time each year, thousands of students came to Changte to take examinations for government positions. Large numbers of them came to the mission, but were full of conceit, disorderly, and impossible to control. Planning to be ready for them the next year, he sent to Shanghai for a large globe, several maps, and astronomical charts. When groups of students came, they immediately asked, "What is that big round thing?" He would explain that it was a representation of the earth. "You don't mean to tell us that the earth is round, do you?" they would reply in astonishment. And when he explained the movements of the earth, some were sure to exclaim, "If the earth turns like that, why don't we all tumble off?" Then followed explanations concerning the law of gravitation, the size of the sun, its distance from the earth, and other astronomical facts. Thus, pride was dispelled and hundreds of students listened attentively to the story of Christ and His redeeming love.

The missionary had a passion for preaching, a longing to develop the converts into New Testament Christians, and a zeal to establish spiritual, indigenous, New Testament churches after the Pauline pattern. Taking a group of native Christians with him, he would "go from town to town and from street to street preaching and singing the Gospel in true Salvation Army style." A map of the field was made and each center where a Christian church or group had come into existence, was indicated by a red dot. By May of 1900, there were over fifty of these red dots. Both parents and children delighted to watch the dots increase. Florence, the oldest daughter, age 7, exclaimed one day, "Oh won't it be lovely, Father, when the map is all red!" The work of God was progressing mightily. "Our hearts are aglow with the victories of the present and the promises of the future, " wrote Goforth. For the hundredth or thousandth time, he quoted his great text, "We expect a great harvest of souls, for it is not by the might, or power of man, but by my Spirit, saith the LORD."

The victories of the present!

The promises of the future!

A great harvest of souls!

It is by my spirit, saith the LORD!

During the early months of 1900, the hearts of the missionaries were radiant with blessing and hope. Then came the storm. In June, golden-haired Florence was smitten with meningitis and "went to be with Jesus." The funeral was scarcely over when a message came from the American Consul in Chefoo saying, "Flee south. Northern route cut off by Boxers." The terrors and horrors of the infamous Boxer Uprising were descending. The missionaries were in favor of staying at their post regardless of the consequences, but the Chinese Christians made it clear that their chances of escape would be greatly reduced if the missionaries remained. On June 28, before daybreak, the missionary party, consisting of the Goforths and their four children, plus three men, five women, and one little boy, set out on the long and hazardous fourteen-day journey by carts to Fancheng and a longer period from there by boat to Shanghai. There were days of panic and agony due to the intense heat, the long hours of continual bumping over rough roads in spring less carts, the illness of one of the children, and the oft repeated cries, "Kill these foreign devils" that came from fierce, threatening mobs along the way.

At one point, a mob of several hundred men attacked them with a fusillade of stones. As Goforth rushed forward to try to reason with the men, he was struck on the head and body by numerous savage blows and one arm was slashed to the bone in several places. Dripping with blood, he staggered to the cart, picked up his baby and said, "Come! We must get away quickly." Rosalind and other missionaries received very painful injuries but all managed to escape as the mob scrambled for their possessions in the carts.

After many terrifying experiences and narrow escapes, they reached Shanghai and soon sailed for Canada. The furlough was a time of poignant sorrow as Goforth, in his deputation trips, found that worldliness and apostasy had invaded the churches and most of the people had little concern for the unsaved masses of heathen lands.

Back to China they went, to the people they loved, to the multitudes they yearned to win to Christ, to the land where all their possessions had been destroyed four times, and where four of their children were buried. Jonathan was soon enthused over a plan of intensive evangelism which would entail their staying in successive centers for a period of one month each. "I will go with my men," he said to Rosalind, "to villages or on the streets in the day time, while you receive and preach to the women in the courtyard." The evenings would be devoted to open air meetings.

At the end of a month, an evangelist would be left to instruct the converts and establish a congregation. "The plan sounds wonderful," replied Rosalind, "except for the children. Think of all the infectious diseases and of our four little graves. I can't do it. I cannot expose the children like that." He, however, was sure of God's leading in the matter and said, "Rose, I fear for the children if you refuse to obey God's call and stay here at Changte. The safest place for you and the children is the path of duty." A few hours later, Wallace became seriously ill with Asiatic dysentery. After two weeks, he began to recover and Jonathan packed up and set out on tour alone. The next day, the baby Constance fell ill. The father was sent for. Constance was dying when he arrived. Driven by sorrow, Rosalind leaned her head upon the Heavenly Father's bosom and prayed, "O God, it is too late for Constance; but I will trust you hereafter for everything, including my children."

Thenceforth, for years she and the children traveled almost constantly with Goforth in his extensive evangelistic tours. This meant that some things loved and prized by the family had to be given up, such as flowers, a bird, a dog and a cat. It also meant living simply in native Chinese style. Usually, the furnishings of the rented native house consisted one table, two chairs, a bench for the children, and the kang – a long brick platform bed covered with loose straw and straw mats, where the entire family slept; that is, if the vermin, insects and pigs permitted them to do so!

Goforth's evangelistic methods were simple and spiritual. Whether speaking to one person or a thousand, he was never known to attempt to deal with souls without his open Bible. His love for and dependence upon the Word is indicated by the fact that he read through and studied his Chinese New Testament fifty-five times in one period of nineteen years. In addition to short Gospel messages and testimonies, he also used large hymn scrolls as a means of utilizing the people's love of singing and of teaching the great truths of the Gospel. In every place where they lived as a family, they carried on this type of intensive evangelistic effort and a growing church was subsequently established.

At the age of forty-four, a strange restlessness came over Jonathan Goforth. He had seen hundreds of precious souls saved and scores of churches established. But his soul burned with an indescribable longing to enter into the fulfillment of his Lord's promise, "Verily, verily, I say unto you, he that believeth on me, the works that I do shall he do also and greater works than these shall he do." Tidings of the mighty revival in Wales intensified this longing, as did also a booklet containing selections from Finney's Lectures on Revival. Again and again, he read Finney's argument that the spiritual laws governing a spiritual harvest are as real and dependable as the laws of agriculture and natural harvest. At length he said, "If Finney is right, and I believe he is, I am going to find out what these spiritual laws are and obey them, no matter what the cost may be." He began an intense study of every passage in the Bible dealing with the Holy Spirit. He arose regularly at five o'clock or even earlier for Bible study and to pray for the fullness of the Spirit. One evening while speaking to an audience of unsaved people on "He bare our sins in His own body on the tree," he saw deep conviction written on every face and almost every one took an open stand for Christ. Shortly thereafter, he visited Korea and was stirred by participation in remarkable outpourings of revival power.

In 1908, he accepted invitations to conduct revival efforts in Manchuria. He did not deal in pious flattery. He told of the amazing results in Korea – of dynamic New Testament Christianity, of the quality and astounding increase of converts, of schools and churches, all self-supporting, and he pointed out the humiliating contrast in the paucity of spiritual results in Manchuria. Wherein lay the difference? It could not be accounted for on ground of war and political unrest in Manchuria, for Korea had had her full share of these. The marvelous results in Korea, he emphasized, were "not by might, nor by power, but by my spirit, saith the LORD." The difference was in the degree of yieldedness to the Spirit and of readiness to pay the price of spiritual power. Goforth himself had paid that price – in prayer and in penitence. A spirit of estrangement had arisen between him and a fellow missionary. When he tried to preach the Lord spoke to him, "You hypocrite. You know you do not really love your brother. If you do not straighten this thing out, I cannot bless you." Realizing that he was just beating the air, he yielded and said, "Lord, just as soon as this meeting is over, I'll go and set this matter straight." Instantly, God's power surged upon him and his preaching was "in the demonstration of the Spirit." Upon the meeting being thrown open for prayer many arose to pray, only to break down weeping. "For almost twenty years," said Goforth, "we missionaries in Hogan had longed in vain to see a tear of penitence roll down a Chinese cheek." He did effect a full reconciliation with his fellow missionary and thenceforth the Spirit could use the yielded, cleansed life.

Those were days of unprecedented spiritual awakening. As a result, he was deluged with invitations from all parts of China and found himself drawn into a new and far-reaching type of ministry. Rosalind and the five children sailed for Canada and he, a lonely man, separated from his family 'till his next furlough time, plunged into the greatest work of his life.

One day at the close of his message, he said to the people, "You may pray." Immediately an elder of the church, with tears streaming down his cheeks, stood before the congregation and confessed the sins of theft, adultery, and attempted murder. "I have disgraced the holy office," he cried. "I herewith resign my eldership." Other elders, then the deacons, arose one by one, confessed their sins and resigned. Then the native pastor stood up, made his confession and concluded, "I am not fit to be your pastor any longer. I, too, must resign." As the Christians confessed their sins and got right with God, large numbers of unbelievers came under deep conviction and were saved. Some of the missionaries were entirely out of sympathy with these revivals. One man said, "Don't expect any such praying and confessing of sins here as took place in Mukden and Liaoyang. We're hard-headed Presbyterians from the North of Ireland and the people take after us. Anyhow, we have respectable people here, not terrible sinners. Be prepared for a quiet Quakers' meeting at this place." But several days later, the Pastor and many others sobbed out their confession, the whole congregation did the unheard of thing of getting down on their knees in prayer, and there was a mighty turning to God in that place.

Many times there was so much praying and confessing,, little or no time was left for the message; even so, the meetings often lasted for three, four, or even six hours. At Kwangchow, God's Spirit worked mightily; the church was cleansed and edified, one hundred fifty-four converts were baptized during the eight days' meeting, and the number of Christians in this city increased in four years from 2,000 to 8,000. At Shangtehfu, there was an intense desire on the part of missionaries and Chinese Christians alike for a blessing from Heaven. Long before daylight, the pleadings of earnest hearts arose to the throne of grace. One missionary sobbed out his prayer, "Lord, I have come to the place where I would rather pray than eat." In this place, five hundred people openly acknowledged Christ as Savior. In a mission school where at first there was much antagonism, scores of boys were brought under the conviction of the Spirit, confessed their sins, accepted Christ, and brought a huge pile of pipes, cigarettes, and tobacco to be destroyed. They also brought stolen knives and other things to be returned to their rightful owners.

Dr. Walter Philips, who at first was prejudiced against the revival movement, wrote of the meetings at Chinchow, “Now I understood why the floor was so wet – it was wet with pools of tears. Above the sobbing of hundreds of kneeling penitents, an agonized voice was making pubic confession. Others followed. The sight of men forced to their feet and impelled to lay bare their hearts brought the smarting tears to one's own eyes. And then again would swell the wonderful deep organ tone of united prayers, while men and women, lost to their surroundings, wrestled for peace.”

Dr. P. C. Leslie said, "It was touching to see the distress of these pillars of the church, weeping in the presence of men because they had been humbled in the presence of God." Like the disciples at Pentecost, they were filled with the divine fullness and anointed with the Spirit's power.

Weeping in the presence of men!

Humbled in the presence of God!

Filled with the divine fullness!

Anointed with the Spirit's power!

One of the songs Jonathan loved was this:

Lord, Crucified, give me a heart like Thine;

Teach me to love the dying souls around,

Oh, keep my heart in closest touch with Thee;

And give me love pure Calvary love,

To bring the lost to Thee.

Those who, like Paul, have as their one sublime obsession the bringing of lost souls to Christ, are sure to endure many trials. It was so of Goforth. His trials included severe attacks of various diseases, intense suffering from chronic carbuncles, beatings at the hands of Chinese mobs, long periods of separation from his family, and the burial of five of his children in China. Another sore trial arose in connection with his furlough visits to the home land, as he came to realize the appalling inroads of modernism and worldliness among the churches and the consequent apathy, even hostility, to his pleadings for missionary advance and a deeper work of the Spirit of God.

Speaking at the ministerial association of a certain city, he told of the Spirit's quickening, purifying, and energizing work in China. He made it clear that he was no special favorite of the Almighty, that the same God was ready to pour out His Spirit in blessed revivals in Canada, and that it was the business of every minister to look to the Holy Spirit for revival in his own heart and among his people. He went on to point out that John Wesley and his colleagues were just ordinary men until their hearts were touched by the divine fire. At that point, a noted Methodist minister interrupted him. "What, sir!" he exclaimed, "Do you mean to tell me that we don't preach better now than John Wesley ever did?" "Are you getting John Wesley's results?" Goforth asked.

The furlough of 1924 was spent chiefly in extended tours through the United States where he was enthusiastically received. His last years on the field were years of great harvest. As he traveled extensively in China and Manchuria, thousands were born into the kingdom and other thousands experienced the peace and power of the Spirit. On a single day, he baptized 960 soldiers. A number of thriving churches were established. All of this was accomplished in spite of many hardships and much pain. During the 1930-1931 furlough, he lost the use of one eye and underwent many painful but fruitless operations in an attempt to restore his sight. During this time of illness, he dictated the stirring stories found in Miracle Lives of China. All his teeth had to be extracted and he contracted a severe infection in his jaw. It was at this time, while pacing the floor and holding his jaw with his hands, that he dictated the material for his famous book, By My Spirit. In China, he contracted a severe case of pneumonia while preaching to a packed audience of sneezing, coughing people in an unheated room in the dead of winter. In 1933, he lost the sight of the other eye. Even during winter blizzards, he continued traveling and preaching. At Taonan, he was led twice or three times daily through the deep snow and the storm to his appointments. A year later, the Goforths returned to Canada because of a breakdown in Rosalind's health. Despite his blindness, he traveled widely in Canada and the United States. Everywhere he went, his soul was aglow with one message, "the fullness of the Christ-life through the Holy Spirit's indwelling." Physical sight was gone, but his life was as a "shining light, that shineth more and more unto the perfect day."

That blessed day dawned for him in the early morning of October 8, 1936, as he slept. Just a few weeks before at the Ben Lippen conference in North Carolina, the sightless veteran missionary said that he rejoiced in the thought that the next face he would see would be that of his Savior. He had entered into the bliss he had long anticipated: "I shall be satisfied, when I awake, with Thy likeness" (Psalm 17:15). That was, indeed, his "coronation day," as Dr. Armstrong said at the funeral service in Knox Church, Toronto, and in the words of Dr. Inkster, "Goforth was baptized with the Holy Ghost and with fire. He was filled with the Spirit because he was emptied of self."

The bliss he had long anticipated!

The Saviour's face! The Saviour's likeness!

Filled with the Spirit!

Emptied of self!

His Coronation Day!

Jonathan Goforth's epitaph, written by the fingers of angels in letters of flaming lights, stands as summons from heaven to all who read:

"Not by might, nor by power, but my Spirit, saith the LORD."

There is a voice of Truth which can be heard crying out! Whether lost or saved, we believe you will meet the living Christ through this ministry.

There is a voice of Truth which can be heard crying out! Whether lost or saved, we believe you will meet the living Christ through this ministry.