Johanna Veenstra - Part 1

A golden-haired, blue-eyed girl, overwhelmed by awe and confusion, stood at the bed of her beloved father as he talked of meeting his Savior in Heaven. For only seven months, he had served as the pastor of a Christian Reformed Church in the state of Michigan, U.S.A., when he succumbed to an attack of typhoid fever. Life was not the same after this to Johanna Veenstra, and she became a source of anxiety to her widowed mother. Often in school she was disobedient and rebellious, and so insubordinate a scholar was she in the Sunday School that her teachers were forced to expel her.

Johanna had come into the world in 1894, in Paterson, New Jersey. This was a Dutch section, said to have produced more workers for God according to its population, than any other part of the city. Between the ages of fifteen and sixteen, she secured a position as typist in New York. With a delightful sense of freedom and money of her own, she yielded to an increasing love of the world and its pleasures. She purchased dresses of the latest fashion, with accessories of jewelery. Not that these things were sinful, but her heart did not belong to the Lord, therefore she became obsessed with these things. She began to frequent the theater and was about to indulge in dance, when she was peremptorily and startlingly arrested by the voice of God in the single word “STOP!”.

Johanna had come into the world in 1894, in Paterson, New Jersey. This was a Dutch section, said to have produced more workers for God according to its population, than any other part of the city. Between the ages of fifteen and sixteen, she secured a position as typist in New York. With a delightful sense of freedom and money of her own, she yielded to an increasing love of the world and its pleasures. She purchased dresses of the latest fashion, with accessories of jewelery. Not that these things were sinful, but her heart did not belong to the Lord, therefore she became obsessed with these things. She began to frequent the theater and was about to indulge in dance, when she was peremptorily and startlingly arrested by the voice of God in the single word “STOP!”.

About to conclude the day's work in the office, Johanna was summoned to the telephone. She recognized the voice of her minister, asking her to come to his home that evening. Much to her own surprise, for at that period of life she had no desire for God, she thanked him and accepted the invitation. When she reached the doorstep of the parsonage, though she scarcely knew why, she was trembling most violently. His fatherly, kindly manner put her at ease, however, his evident concern for her soul brought her to tears and, after a time of prayer, she bade him goodnight.

That visit meant a turning point in her gay thoughtless existence. For almost a year, she lived more or less under a sense of a burden of sin. After the day's work, she often slipped away from the rest of the family to pray. One evening, her sister, curious to know what she was doing, peered through the keyhole of the door of the bedroom to which Johanna had retired and saw her on her knees. Johanna frequently was unable to sleep, gripped with a dreadful fear of death and Hell!

At length, came a divine revelation, convincing her that the reason she could not find rest of soul was that she was not submitted to God and His will. In other words, she sought relief from the guilt of sin, with its attendance of joy, but without the price of complete surrender. The struggle that followed was most poignant. But when Johanna looked up to Heaven, exclaiming through her tears, “Anything, Lord,” her heart was at once eased of it's load, and an assurance of pardon was hers.

Her life no longer was a giddy pursuit for pleasure, but rather one of service to God. Until she was nineteen years of age, several nights a week and Saturday afternoon, she found great happiness assisting Mr. Peter Stam of the “Star Of Hope Mission” in Paterson. Peter Stam was the father of John Stam who, with his wife, Betty, would later martyred in China in 1934. John Stam was only a small child at the time Johanna was helping Mr. Stam at the mission.

When the young woman entered the Union Missionary Training Home in Brooklyn, New York, she was not at all certain that full-time Gospel service was God's plan for her. For three weeks after enrollment, Johanna could not bring herself to unpack her trunk. But all doubt was removed when the words of Jesus were impressed upon her, “No man, having put his hand to the plow, and looking back, is fit for the Kingdom of God.”

During her second year at the school, she represented the students at a Missionary Conference in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. One of the speakers was Dr. Karl Kumm, brother-in-law to Geraldine Taylor, well-known author for the China Inland Mission. In a large area of Central Africa, he had not met a single missionary of the Cross and was greatly burdened for the evangelicalism of its numerous heathen tribes.

Johanna listened to Dr. Kumm addres with breathless interest. As he depicted the condition of scores of dusky African tribes dying outside the pale of the Gospel, her heart was moved. At the close of the service, she retired to her tent, where she spent three days alone in communion with God. Then she knew that, in “the heart of the Eternal”, her field of service was to be Nigeria.

Johanna listened to Dr. Kumm addres with breathless interest. As he depicted the condition of scores of dusky African tribes dying outside the pale of the Gospel, her heart was moved. At the close of the service, she retired to her tent, where she spent three days alone in communion with God. Then she knew that, in “the heart of the Eternal”, her field of service was to be Nigeria.

Johanna was not permitted, however, to go to the African field until she was twenty-five. So the next three years were spent in training for midwifery and in work with a city mission that acquainted her with almost every conceivable type of Gospel effort. She took the message of the Cross to rescue homes, prisons, hospitals, gipsy camps and even into the houses of ill-fame and opium (prostitution and drug houses) in Chinatown of New York City. In October, 1919, she said good-bye to her native land. An unforeseen delay in passage detained her in England for three months but, in the early part of 1920, she reached Lagos, with its former reputation as the largest slave depot on the western coast of the “Dark Continent”.

But before she reached her appointed station in Central Africa, a long journey awaited her. At Ibi, welcomed by the Field Secretary of the Sudan Interior Mission, she was told that her final assignment was to be the Takum district where, among cannibals, the Mission hoped soon to gain a foothold for the Gospel. It was more than a year before she reached the place of her designated labor. But the time was not wasted, for in the interval, she became so skilled in the Hausa language that, in six months, she was able to preach in that tongue.

During this period, Johanna also reached the most important crisis of her life, one which ever after set her apart from ordinary Christians. Spending much time in prayer, she was led by the Holy Spirit to a clearer comprehension of His work upon the human heart than she had previously understood. The perusal of two books on His work and witness created in her an intense hunger to be crucified with Christ. She read and reread again the two books. Eva Stuart Watt, her biographer, said of this search:

“Then she saw that the work she had come to do was not hers at all, but the Holy Spirit's. He had been sent from Heaven to reveal Jesus to the hearts of men. All He needed was instruments willing to be used. She could preach to the heathen for a life-time and preach well, but never convince one of them. She could wear herself out working and yet reap no harvest. He came to convince of sin. He came to do the reaping. Would she allow Him to break her and empty her and then to work through her? Eternity and eternity only, will tell the sacred value of those lonely evenings with God; but Johanna confided to a fellow-missionary the blessing God gave her through the challenge of those books. It meant nothing less than her complete abandonment to the Holy Ghost and His coming in to dwell in her heart.

The Holy Spirit had introduced Johanna to the place that lies within the veil, and she said never an hour passed but that she was conscious of the immediate presence of God. A friend wrote her: “I'm convinced that the inner closet was the secret of her success as a missionary. It was this frequent and oft converse with her Lord that made her so confident on the battle front.” She had learned her own nothingness and henceforth drew upon her inexhaustible supplies in Christ. “The flickering, self-life” was extinguished by “the blaze” of God's glory, and Johanna could say with St. Paul, “The world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world.”

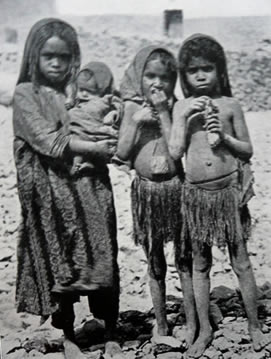

In February of 1921, Johanna set out for her desired haven. With porters to carry the baggage, her means of transport was a bicycle. The area to which she was assigned was in view of the Cameroon Mountains, with many small villages in the foothills, where the Prince of Darkness apparently reigned. Demon-worship was prevalent, and the blood of frequent human sacrifices seemed to call to Heaven for vengeance. Child marriages and polygamy were the usual practice. One chief was said to have ninety-three wives.

In February of 1921, Johanna set out for her desired haven. With porters to carry the baggage, her means of transport was a bicycle. The area to which she was assigned was in view of the Cameroon Mountains, with many small villages in the foothills, where the Prince of Darkness apparently reigned. Demon-worship was prevalent, and the blood of frequent human sacrifices seemed to call to Heaven for vengeance. Child marriages and polygamy were the usual practice. One chief was said to have ninety-three wives.

“I won't dwell on the darkness,” she wrote home. “I couldn't if I tried, but sometimes – I say it solemnly – sometimes I have felt as if I were being drawn through the very gateway of Hell itself . . . I do so want to learn the lesson of letting the Lord carry the burdens for me – not just because that is the easiest way, but because it is His choice. I am so slow to learn these precious lessons.”

Prayer was her solace and strength. The routine of the day's work, with household planning, morning services for the native help, classes for the children for the nearby villages, frequent calls for medical aid – all was preceded by secret prayer for an hour or more. Before dawn, Johanna would spend time meditating, a small hurricane lamp shedding its light on God's Word. In the stillness of the morning watch, she caught a glimpse of the Almightiness of the Lord of Hosts and she knew He was on the battlefield with her.

Take From :

"They Knew Their God" Vol. 1

By: Edwin & Lillian Harvey

There is a voice of Truth which can be heard crying out! Whether lost or saved, we believe you will meet the living Christ through this ministry.

There is a voice of Truth which can be heard crying out! Whether lost or saved, we believe you will meet the living Christ through this ministry.